|

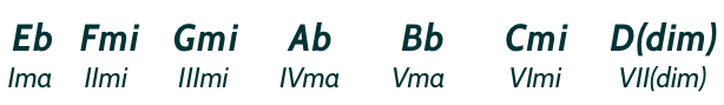

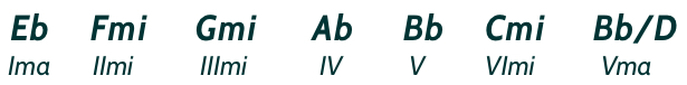

This is among the first things we learn in a collage level study of Harmony: This is the result of stacking the 'C' Major Scale in 3rd intervals (up to the Triad). Every Major Scale creates this unique (and identical) group of chords (by formula). The 'sound' of this grouping of chords must be absorbed into our ear's memory. We learn to identify the sounds (at first) by giving each chord a number (a 'Roman Numeral' that represents a 'sound' within a key - by formula). We call each numeral: a "Chord Function" (to connect the ear with the memory of the brain). There are two points to be made here that are not necessarily explicit in the textbooks: The first is about easy memorization of formula: I, IV, & V are always Major Triads --- and --- II, III, & VI are always Minor Triads -- and -- VII is always a Diminished Triad. The second point is about the ear: Any Major triad that we ever hear in our lives - will "most naturally" be heard as either: Ima, IVma, or Vma (in a Major key). --- and --- Any Minor Triad that we ever hear in our lives - will "most naturally" be heard as either: VImi, IImi, or IIImi (in a Major Key). a Cma Chord (for instance) will be heard as either: Ima in the key of 'C' Major ('C' Ionian); IVma in the key of 'G' Major ('C' Lydian); or Vma in the key of 'F' Major ('C' Mixolydian). a Dmi Chord (for instance) will be heard as either: VImi in the key of 'F' Major ('D' Aeolion); IImi in the key of 'C' Major ('D' Dorian); or IIImi in the key of 'Bb' Major ('D' Phrygian). As for the VII(dim.) triad -- though it is rarely heard in popular music (by itself) - it is the only chord type of its kind within this group of 'Diatonic Triads.' It's uniqueness allows the ear the luxury of certain orientation (certain function within a key). Because it is unique -- the ear uses it to identify (without a shred of ambiguity) the key of its 'function.' It is the reason we see (for example) the '7' in a 'G7.' --- When we see a G7 in a chord chart -- that '7' is an indication of a Vma chord function. Whether we actually 'play' the '7th' tone (beyond the triad) depends on whether we want to hear the tone of 'Fa' (an active melodic tone) in the harmony as it progresses. [Take care not to confuse the '7' (a singe extension tone) and the VII(dim.) (a 3-note triad). For the purpose of this discussion - the VII(dim.) triad is thought of as being combined with the Vma triad. --- In the key of 'C' Major - this would be G,B,D (Vma) combined with B,D,F (VII(dim.)). The tones of the G7 chord are: G,B,D,F -- the 'F' note is the extension tone we call '7' -- and is the tone 'Fa' within the key]. This is keeping it simple -- focusing on the ear's response (and early training) to 'Diatonic Harmony' (harmony of the Major Scale). "Diatonic Harmony" is often referred to as "Modal Harmony" (the two terms are [virtually] interchangeable.

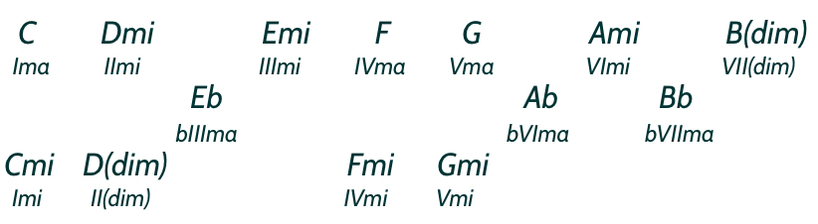

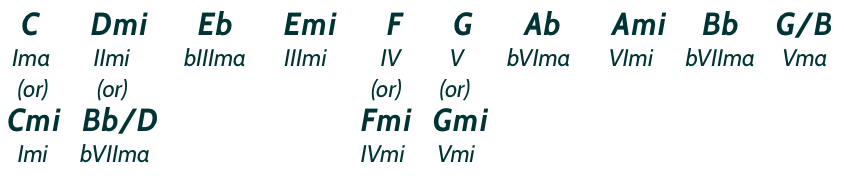

We begin with the Diatonic Triads of 'C' Major (Ionian) 'Aeolian' is the mode that uses the 'Root' (the 'Tonic') of the 6th 'degree.' This means that the VI Chord becomes a I Chord. But before we change the Chord Function(s) - let's look at the Diatonic Triads of Aeolian in their native habitat... their Relative Major Scale. Now let's begin the work of understanding the Aeolian Mode as its own Key Center from the Tonic of 'A': By Formula - the 'A' Major Scale is constructed: When we remove the sharps (to get back to the notes of 'C' Major) -- we get the following formula: This is the Formula for the Aeolian Mode: 1,2,b3,4,5,b6,b7 --or -- Major Scale (b3)(b6)(b7)... it's ok to memorize this because it will never change. Now, let's take a look at how the Diatonic Chord Functions of Aeolian have changed -- when it is considered to be its own Key Center [with 'Ami' functioning as the Tonic (the I Chord)]: We might ask: Why bother learning two different chord functions for the same diatonic chords? The answer: because it changes the way they are heard (remember - this is all about training the ear). Even though the bVIma Chord of the Relative Minor Key Center is really just a IVma Chord in the 'Mother Scale' -- the root movement (in the bass) of a bVIma returning to its Tonic (Imi chord) sounds very different than the root movement of a IVma returning to its Tonic (Ima). There is also something else to be mindful of at this point: any Minor Triad that we ever hear in our lives - will (most naturally) be heard as a VImi - IImi - or IIImi - in a Major Key Center - or - as a Imi - IVmi - or Vmi in a Minor Key Center. Likewise - any Major Triad that we ever hear in our lives - will (most naturally) be heard as a Ima - IVma - or Vma in a Major Key Center - or - as a bIIIma - bVIma - or bVIIma in a Minor Key Center. This discussion has been about 'Relative Minor' (often referred to as 'Natural Minor'). Because the chord types have not changed within the diatonic sequence - it can be said that this discussion has been limited to 'Aeolian' - and could also be referred to as a discussion of Modal Minor or Diatonic Minor. In Part II of this series - we will explore 'Parallel Minor' in a way that is also 'restrictive' to diatonic ideas -- this restriction is for the purpose of training the ear for things to come.

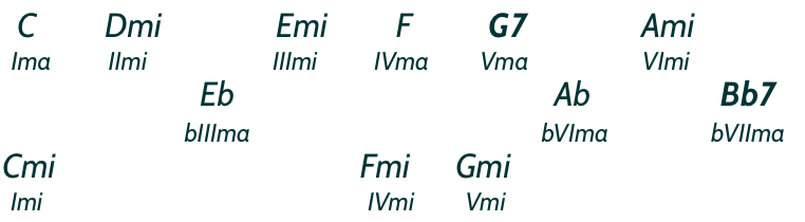

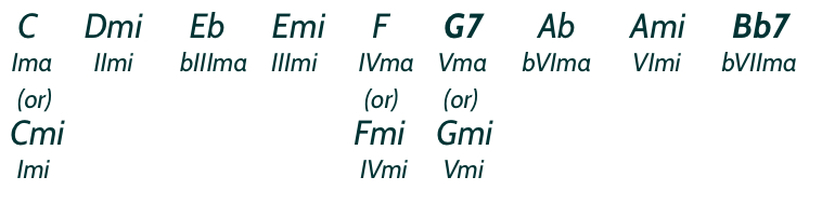

When I hear a melody in my head - the first thing I want to know is: Where's 'Do' (the Tonic)? This tells me whether I'm hearing a Major or a Minor Key Center [this is determined by whether I'm hearing 'me' (b3) or 'mi' (natural 3rd)] - with/against the Tonic. When I first started doing this - I would reference (in my head) any Major sounds to 'C' Major -- and any Minor sounds to 'A' Minor. The reason I chose this reference was because it was comfortable. I used this method - even at times when I was hearing both - Major and Minor sounds (in relation to the same Tonic). I would spare anyone the confusion this caused by suggesting that we become comfortable with the Key Center of 'C' Minor (to get to know the sounds of the direct contrast between a Minor Key Center and a Major Key Center -- that share the same Tonic... the same perspective. Realize that what we're doing here is combining the harmony of Two Major Scales ['C' Major and 'Eb' Major] into a single palette (with a single Tonic) to train the ear. We begin by asking the question: In which Major Scale does the 'C' note reside as the sixth degree? The answer (in the case of Aeolian) is always one whole step + one half step up from the note in question -- this translates to the Eb Major Scale: From the 'Relative Minor Tonic of 'C' - we see: 'C' Minor Now we compare the 'C' Minor Key Center to the 'C' Major Key Center: Here - we begin to move the chords (from 'C' Minor) that offer unique root movement (in relation to 'C' Major) 'up' into a new palette to explore: I find it interesting that the chords in 'C' Minor (Aeolian) that offer 'unique' root movement (in relation to the key of 'C' Major) happen to be the I,IV, and V chords of its Relative Major (Eb Major). As outlined in a previous post - the diminished triad can be heard as an extension of a Vma triad function - as a V7 (Dominant Chord). We can eliminate the diminished triads in our palette by adding the 7th (extension tone) to the V Chords of the two Major Keys we are combining: 'Eb' Major (Bb7) and 'C' Major (G7): So that finally we end up with a palette (of likely chord types - and new possibilities for root movement) that looks like this: Diatonic Triads: Using The Root Movement Of The VII Diminished Triad Without The Diminished Sound11/15/2015

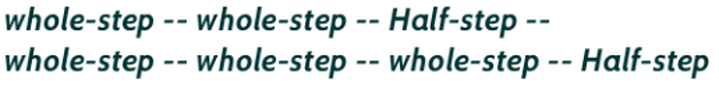

We've established that the VII(dim) can be thought of as the result of combining two triads -- Vma + VII(dim) = V7 (the V7 is just a Vma Triad with one extension tone (7) -- which happens to be 'Fa' of the 'Mother Major Scale.') Because this knowledge becomes useful when we begin to study 4-part harmony -- we've made an attempt to include the VII(dim) Triad Function (in the theory). But, while the sound of the VII(dim) is excellent for ear training -- the 'angular' sound of the Diminished Triad is not commonly heard in the context of modern modal harmony. However, the functional root movement (VII in the bass) is absolutely essential in modern modal harmony. Here's how we exclude the VII(dim) triad sound while utilizing the 'VII' Function's root movement: The Key Center of 'C' Major ('C' Ionian) would look like this: The G/B is called a 'Slash Chord' -- it is a G Major Triad with the B-note in the bass (it is an 'inversion' of the G triad). [For guitar players - it may help to know that this can be as simple as a two-note chord (G-note with a B-note in the bass -- a minor 6th interval that we all get to know well when we are learning tunes)]. The Key Center of 'A' Minor ('A' Aeolian) would look like this: The Key Center of 'Eb' Major ('Eb' Ionian) would look like this: The Key Center of 'C' Minor ('C' Aeolian) would look like this: The combination of the 'C' Major and 'C' Minor Key Centers looks like this: Maybe this is elementary - but I've always been fascinated with the fact that the musical ear can still distinguish any triad when it is inverted. The Ear Just Knows To illustrate the practical significance of the concept of reciprocity – here are a few exercises you can try using any harmonic instrument such as a piano or a guitar: Exercise 1 1) Strike a ‘C’ note and then the ‘G’ note above. You are now hearing a Perfect 5th interval. This should give the impression of some sort of ‘C’ Chord --- and all is right with the universe. ‘C’ is functioning as the generative fundamental tone – and everything indicates the ‘harmony’ of ‘C.’ 2) Now, strike a ‘G’ note and then the ‘C’ note above. You are now hearing the reciprocal of the Perfect 5th interval - which is a Perfect 4th. This should also give the impression of some sort of ‘C’ Chord -- but something is odd. The ‘G’ note is ‘serving’ as the generative fundamental tone of the harmonic structure, but your ear recognizes the ‘C’ note (the higher tone) as the root of the chord. This is the prime example of the ear naturally negotiating the reciprocity of the Perfect 5th. Now, let’s investigate the ear’s natural harmonic intelligence in discerning the Major 3rd with its interval of reciprocity – the Minor 6th: Exercise 2 1) Strike a ‘C’ note and then the ‘E’ note above. You are now hearing a Major 3rd interval. This should give the impression of some sort of ‘C’ Chord (with a definitive ‘major’ quality) - and all is right with the universe. ‘C’ is functioning as the generative fundamental tone – and everything indicates the ‘harmony’ of ‘C’ (major). 2) Now, strike an ‘E’ note and then the ‘C’ note above. You are now hearing the reciprocal of the Major 3rd Interval - which is a Minor 6th. This should also give the impression of some sort of ‘C’ Chord (with a definitive ‘major’ quality) -- but something is odd. The ‘E’ note is ‘serving’ as the generative fundamental tone of the harmonic structure, but your ear recognizes the ‘C’ note (the higher tone) as the root of the chord. This is the prime example of the ear naturally negotiating the reciprocity of the Major 3rd. Now, let’s investigate the ear’s natural harmonic intelligence in discerning the Minor 3rd with its interval of reciprocity – the Major 6th: Exercise 3 1) Strike a ‘C’ note and then the ‘Eb’ note above. You are now hearing a Minor 3rd interval. This should give the impression of some sort of ‘C’ Chord (with a definitive ‘minor’ quality) - and all is right with the universe. ‘C’ is functioning as the generative fundamental tone – and everything indicates the ‘harmony’ of ‘C’ (minor). 2) Now, strike an ‘Eb’ note and then the ‘C’ note above. You are now hearing the reciprocal of the Minor 3rd interval - which is a Major 6th. This should also give the impression of some sort of ‘C’ Chord (with a definitive ‘minor’ quality) -- but something is odd. The ‘Eb’ note is ‘serving’ as the generative fundamental tone of the harmonic structure, but your ear recognizes the “C’ note (the higher tone) as the root of the chord. This is the prime example of the ear naturally negotiating the reciprocity of the Minor 3rd. Subjectivity & Harmonic Impression At this point it is important to note that as we experiment with intervals (in this context) that are less prominent (audible) in the overtone series; our experience of the initial harmonic impressions become more and more subjective. I will close by describing my subjective impressions of the reciprocity between intervals other than the Perfect 5th and the Major 3rd. The Minor 3rd Interval The Minor 3rd interval - and its interval of reciprocity - the Major 6th - are still quite clear in harmonic definition (probably because of the relative modal implications we are so used to hearing in contemporary music). The Major 2nd Interval The Major 2nd interval – and its interval of reciprocity – the Minor 7th – give me the impression of being Non-Definitive. This means that the root of the harmony is not very clear. To add to the ambiguity of this situation – the character of their sound is Open and Suspended - without the feeling of ‘needing’ to be ‘resolved.’ I have found the exploration of this harmonic interval-pair fascinating over the years. In the key center of ‘C’ – the Major 2nd (‘D’) is the ‘So’ of ‘So’ ---- and the Minor 7th (‘Bb’) is the ‘Fa’ of ‘Fa.’ The Major 7th Interval The Major 7th interval – and its interval of reciprocity – the Minor 2nd – give me the impression of being Non-Definitive. This means that the root of the harmony – when either of these intervals are heard - by themselves – is not very clear. The character of their sound is Closed and Angular - with the feeling of ‘needing’ to be ‘resolved.' This suggests (to me) some form (or modality) of a Dominant Chord. In the key center of 'C' - the Major 7th ('B') is the 'tri-tone' of 'Fa' ---- and the Minor 2nd ('Db') is the 'tri-tone' of 'So.' Taken from the book: 'What Does This Have To Do With Music?' By Ben Higgins Every Major Scale is constructed the same way. For this reason... any Major Scale will sound the same as any other Major Scale. The only difference will be the "Key" (of pitch). The Major Scale is constructed: The Greeks decided long ago that there would be a 'natural half-step' between the notes 'E' - 'F' and between the notes 'B' - 'C' --- This resulted in the 'C' Major Scale being the only major Scale that did not require accidentals (#'s or b's). The 'G' Major Scale requires an 'F#' to complete its construction: This is the only reason for the 'F#' (in the 'G' Major Scale) -- it is not mystical... it is music fact. The Formula for any Major Scale is: By Formula - if the root is 'C' -- the rest of the scale is: By Formula - if the root is 'G' -- the rest of the scale is: By Formula - if the root is (again) 'G' -- and the 'F' is not sharped - the rest of the scale is: This is the Formula for Mixolydian (1,2,3,4,5,6,b7 -- or -- Major Scale (b7). Notice that the construction of whole-steps and half-steps have changed -- even though, only the notes of the 'C' Major Scale are being used. Changing the 'Root' (the 'Tonic') of a given Major Scale (while using only the tones of that major scale) - changes the ear's perception of that Major Scale. This changes the sound... because it displaces the relationship of the half-steps - as they are 'sounded' with (or against) that Tonic. The greatest 'take away' of this 5 page document should be a a better understanding of the terminology involved in describing formulae - as related to Major Scales and Intervals.

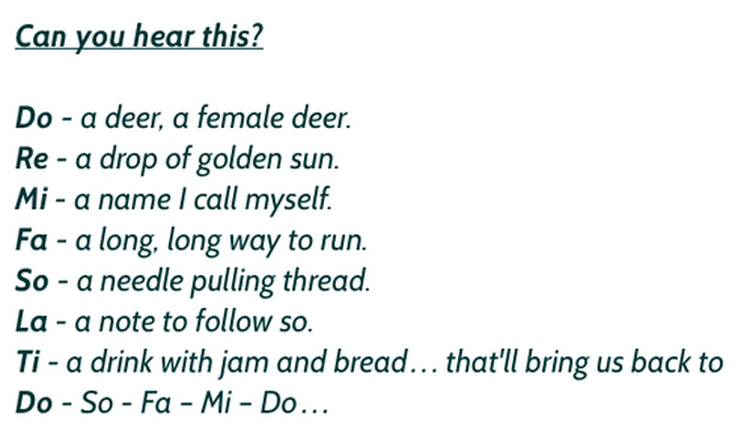

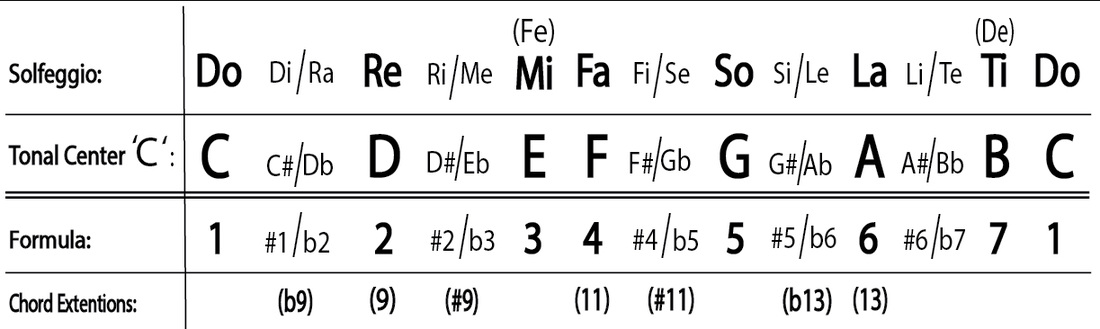

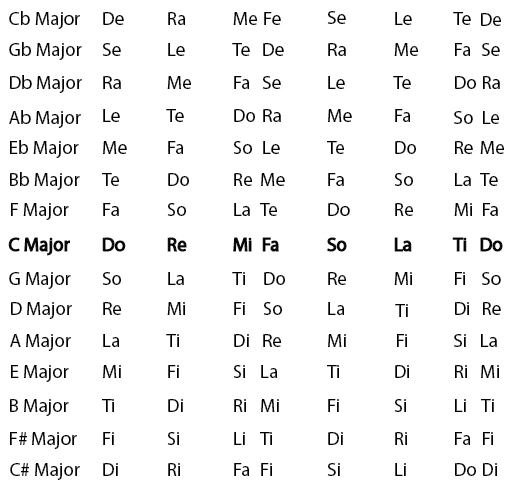

When someone claims to have "Perfect Pitch" -- it's perfectly ok to say, "I'm Sorry!" These musicians can experience unique problems in their early studies of music. What we really desire to possess is "Relative Pitch!" This is something that can be learned through the practice and study of Solfege Syllables. Beethoven, Mozart, and any composer worth their salt did not require the keyboard to compose a melody. They developed their own ‘adult’ version of this children’s song – and they did not, merely, listen to it in their heads… they felt the many combinations of tones resonate within their bodies. You may have thought this ability to be beyond you, but if you can hear this song in your head; you have the same raw material to develop the skills they had. Diligent study of this organon will allow you this kind of ability… and more. Diatonic Chromaticism If you’ve studied music for a while, you have surely learned about the diatonic key center demonstrated in our ‘do re mi’ song. You may have been taught that all tones that are not in a particular Major Scale are considered to be chromatic – and therefore – non-diatonic. While this is a true statement, taken by itself – let’s build all 15 Major key signatures using only the solfeggio that belongs to a single tonal key center: the tonal key center of ‘C.’ From this perspective – we shall see every single chromatic tone included on our palette -– both, sharped and flatted solfege syllables. Taken from the book: 'What Does This have To Do With Music?' -- By Ben Higgins I’ve been disappointed more than once with music notation software. Too often - it can be quite a task to get what I hear in my head into the editor… and too often - the applications overreach by offering playback that never has the same ‘rhythmic feel’ as what I was intending to write. As exciting as these apps can be (with their many powerful features); when I actually attempt to use them - I find them to be more of a ‘drag’ on the creative moment than an inspiring tool. So, I thought… What if I could just pull up a text editor (or ‘word’ program) and put down ideas that are adequately articulate and consistently translatable to any implementation?

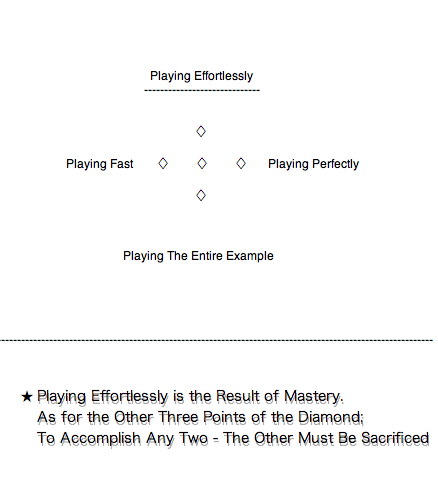

The following is a rudimentary text code I created for this purpose. I call it: ‘Cherry Text’ - or - ‘Cherry Code.’ Click the button below to learn the code: We hear music in two keys at once...  When we first learn that this thing called 'Music Theory' actually exists; our first encounters with it involve grouping designations of notes together and giving these groups of tones names -- such as: Scales, Chords, Triads, Arpeggios, etc... At the college level; we learn to identify with more terms: Dominant, Sub-Dominant, Tonic, Cadences, Resting & Active Tones, etc... All of this rigorous study was designed to develop our ear... and was necessary to develop a vocabulary that musicians may use to communicate -verbally- what they hear. After all is said and done in our 'formal study of harmony' (if we have studied well) --we may come to a fundamental understanding of the way the harmonic overtone series most naturally reacts to melody that is created using elemental tetrachords taken from our Major Scale. For us - there is a difference between music 'theory' and music 'fact.' -- One example of a music fact would be something like: "There are three flatted notes in the 'Eb' Major Scale (according to the design of our equal-tempered 12-tone system)." --- Now, if this statement is taken as a fact, then - What is music theory? We find the implications of the following statement to be in the order of the mystical - and would like to suggest that it represents the heart of true-music-theory... the kind of theory that requires both hemispheres of our brain (and a lot of experience listening and playing) to grasp: 'We begin in the tonal center of 'C' --- When we hear the fundamental tone 'Do' ('C') - the tone 'So' ('G') is heard, physically, as the "Dominant" overtone in the natural acoustics of the harmonic overtone series. This tone ('So') is so "loud" in relation to all other overtones being propagated in the natural harmonic overtone series that the ear 'may' hear all the tones of the ‘C’ Major Scale in relation to the tone 'So' ('G') – as if it were, itself, the “fundamental" (‘Do’). What this means is that the ear 'may' hear the tone 'C' (the true 'Do') as 'Fa' -- and the tone 'F' (the true 'Fa') as 'Te' (a flatted tone). This suggests that any flatted tone may - most naturally - be heard as 'Fa' of a new Major Scale --- and any 'Do' (a resting tone) may also be heard as 'Fa' (an active tone). It also goes without saying that any 'So' may be heard as 'Do.' This is why it can be said that the 'Blues' assumes that this 'Diatonic Pivot' had already occurred before the music began.' We hear music in two keys at once... even though we focus our understanding in one key at a time. There are various misconceptions formed by guitar students (and some controversy among guitar teachers) about the degree of importance that should be ascribed to the ability to read standard notation in today's popular styles. As a teacher, I focus on the ability to read music for the purpose of developing the ear - as well as the ability to 'grasp' new material more quickly - and efficiently (this is the development of the mind). Any preconception that one must become a 'monster sight-reader' to succeed in musical development is just not true. Actually -- I'm not sure there is such an animal --- all of us need to spend some time with a piece before we get a handle on it. The only question is: Will we need 5 minutes... or five hours... or five weeks? I plucked this from a good read called "Effortless Mastery" by Kenny Warner. This is a simple formula for understanding where we are in our practice. When we can play a given piece effortlessly... we have arrived. |

||||||